Chapter 6 Photochemistry

6.0.1 Learning Objectives

At the end of this section you should be able to:

- Show an awareness of excited state reactions and rearrangements.

- Discuss energy transfer, excitons and delayed fluorescence.

- Explain pictorially why the rate of some chemical reactions may be slowed upon promotion to a high excited state.

There are a number of reactions in which light is an essential component, indeed life on earth wouldn’t occur without a photosensitised reaction, nor would we be able to see. This work is little more than an introduction to the fundamental processes, however it should be noted that using light is becoming increasingly important in modern chemistry research. Whether this is for use in sensors, medicine, or energy production the fundamental concepts are largely the same, and these concepts are introduced here.

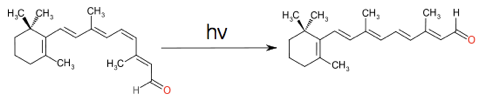

6.1 Photoinduced Isomerisation

When discussing the absorption of light it was noted that by promotion of an electron into an anti-bonding orbital the bond order was reduced. In the case of double (π) bonds in molecules such as retinal (figure), the bond order of one of the double bonds is reduced and therefore allows rotation around this now single bond, as the energy is lost (either by internal conversion or emission) the π-bond is restored. A simple Lewis model of bonding is convenient, however we have to consider the molecular orbital, and this version of bonding highlights a particular bond which is weakened in the excited state, consequently rotation occurs around a specific bond in a conjugated chain.

Figure 6.1: The cis-trans isomerisation of retinal, which when combined with the protein rhodopsin is vital in vision. Absorption of a photon, reduces the bond order of a specific bond due to characteristics of the excited state molecular orbital.

The steady state photochemical yield of any such cis-trans isomerisation will depend upon the absorption of each of the chromophore isomers at the excitation wavelength, the composition of this steady state is referred to as the photostationary state. The composition of this photostationary state may be easily calculated making only minor assumptions.

The most important of these assumptions is that when in the excited state there is an equal probability that the molecule will relax to the cis & trans states. The second assumption is that (near) monochromatic light is used, because we have already seen that the molar extinction coefficient is very wavelength dependent. Finally the excitation has to occur long enough for the (steady state) photostationary state to be established.

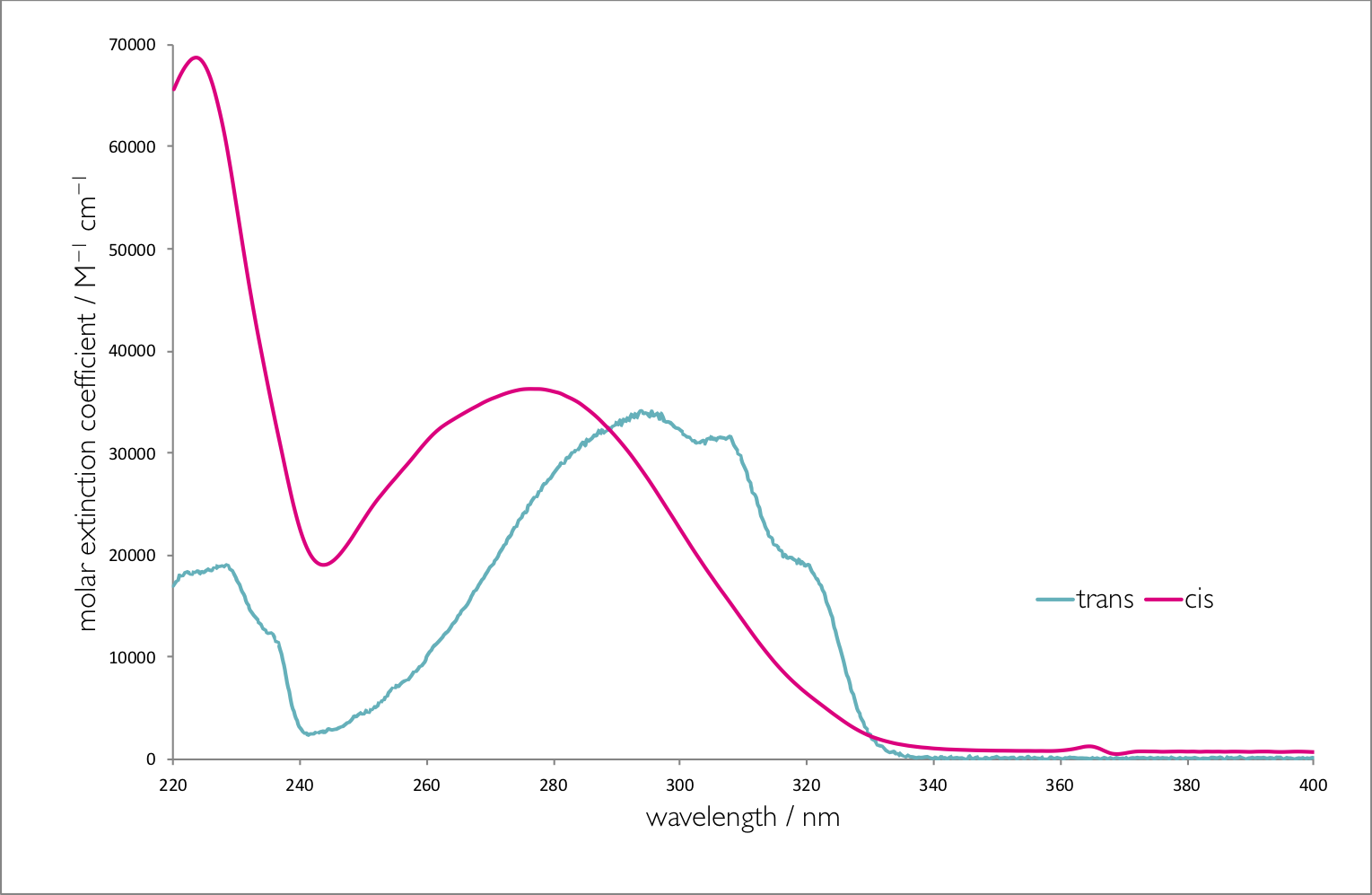

Figure 6.2 shows the absorption spectra of the two isomers of stilbene, there are a number of interesting photophysical details about this molecule, but it should be noted that the molar extinction coefficient is different for each of the isomers. The point where the two spectra cross is called the isobestic point , for stilbene this is 288 nm, if the system is excited at this wavelength then the yield of each isomer will be the same. However at all other wavelengths the yield of one isomer will be higher than the other. If an excitation wavelength is used whereby the molar extinction coefficient of the trans isomer is highest then this isomer is excited preferentially and there is less of this isomer is the photostationary state.

Figure 6.2: The absorption spectra of trans and cis stilbene in hexane.

In summary the higher the molar absorption coefficient at the excitation wavelength the lower the yield of that product in the photostationary state.

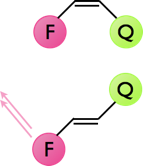

The dynamics of cis-trans isomerisation may be studies by using some of the photophysics already discussed. Figure 6.3 shows a cis / trans system, in the cis position the emission from a fluorophore is quenched so there is no visible emission from the dye. In the trans position position of the quencher now means that there is either no quenching or the quenching is greatly reduced, consequently the emission from the fluorophore is greatly increased.

Figure 6.3: The quenching of emission of a fluorophore by a nearby quencher, in the cis configuration the emission from the fluorophore is completely quenched, whereas in the trans configuration emission from the fluorophore is observed.

6.2 Photoinduced Rearrangements

Cis / trans isomerisations are not the only type of photochemical reaction; dienes, trienes and polyenes often undergo structural isomerisation, specifically cyclisation reactions. Upon excitation 1,3-butadiene undergoes a ring closing reaction to form cyclobutene. This reaction only occurs from the cis isomer, the trans isomer will instead rearrange as described above.

Reactions of polyenes are highly dependent upon the electronic configuration of the excited state with chemistry from singlet states being very different to chemistry from triplet states. The longer lived triplet states frequently undergo second order dimerisation reactions, whereas the singlet states lead to a internal single molecule cyclisation reactions.

Direct absorption of light may only lead to one of the possible products, for systems with a low triplet yield it is not easy to undergo dimerisation reactions, even if this is the desired products. Instead of direct absorption of light, which frequently only leads to the singlet state, a photosensitiser may be used, use of a sensitiser is common for selective reactions of alkenes or aromatic compounds.

A triplet sensitiser may induce a triplet state in another molecule by energy transfer. A sensitiser molecule maybe excited and relax, via intersystem crossing into an excited triplet state. This sensitiser then undergoes an energy transfer reaction with the ground state alkene molecule. Since the sensitiser was in a triplet state the excited state alkene will also be in a triplet state, and now reaction products of the excited state may will be different from products of the singlet excited state.

One thing to note for photosensitised reactions is now the photostationary state yield has nothing to do with the absorption coefficient of either of the states. Consequently if a products has to be isometrically pure a sensitiser is often used to ensure high yields of only one of the photoactive isomers.

6.3 Photoinduced Electron Transfer

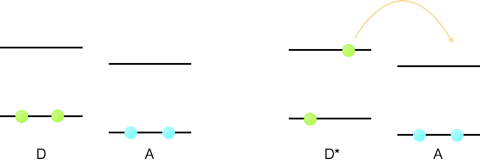

Redox reactions are an incredibly important class of chemical reaction with the simplest of these being movement of a single electron from a donor (oxidiser) to an acceptor (reduced). In a redox process we are effectively removing an electron from the HOMO of a donor, to an infinite distance (where there are no charge charge interactions, recall definitions of ionisation energy), and then returning that electron from infinity to the LUMO of an acceptor molecule. Redox reactions have traditionally occurred if you get more energy back from the reduction than it takes to oxidise the donor.

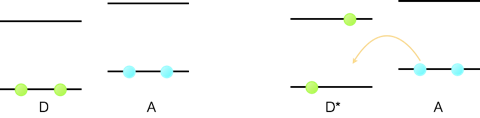

However, if we excite an electron from the HOMO into the LUMO then the energy it takes to oxidise the molecule is reduced. Consequently a molecule in its excited state is a better reducing agent than a molecule in its ground state, and redox reactions that cannot occur from the ground state can occur from the excited state, figure 6.4.

Figure 6.4: The one electron redox reaction of a donor molecule, D, and acceptor A. For the ground state the empty LUMO is higher in energy than the donor HOMO and so no reaction occurs. Upon excitation of the dye, D*, the donor electron is now higher in energy than the empty LUMO and so the one electron transfer reaction can occur.

This is not the only mechanism by which an excited state can lead to movement of an electron between two molecules. Figure 6.5 shows a hole transfer reaction (movement of a vacancy), where by a chromophore is excited and an electron moves from a second molecule into the hole left behind in the HOMO orbital.

Figure 6.5: A hole transfer reaction, where a molecule is excited an the electron transfers from the ground state HOMO orbital of a second molecule into the vacancy in the HOMO orbital of the excited chromophore.

Since the electron moves between the two molecules there has to be an overlap between the molecular orbitals of the donor and acceptor molecules.

The Rehm-Weller equation (equation (6.1)), relates the driving force of a photochemically promoted electron transfer reaction to the redox potentials of the donor (reducing agent Eº(D•+/D)) and the acceptor (oxidising agent Eº(A/A•−) and the energy gained by promotion of an electron into a LUMO orbital (E0,0, quite literally the energy between the ground and excited electronic states for the v=0 bands). There is a small correction factor required, ω(r) but in polar solvents this is negligible, e is the elementary charge on an electron, so in this form this is the driving force for movement of a single electron. This process is normally called photo induced electron transfer.

\[\begin{equation} \Delta G ^\circ = e[E^\circ(D^{\bullet +}/D)-]E^\circ(A-A^{\bullet -})]-E_{0,0} + \omega (r) \tag{6.1} \end{equation}\]

6.4 Marcus Theory of Electron Transfer

The rates of other mechanisms of excited state reactions have all been detailed in chapter 4, but so far, whilst I have described the mechanisms of electron transfer between a donor and an acceptor we have not quantified the rates of these reactions.

The rate of electron transfer was found to depend upon a number of factors described by the Marcus equation (6.2).

\[\begin{equation} k_{et}=\frac{2 \pi |V(r)|^2}{h}\frac{1}{\sqrt{4 \pi \lambda k_B T}}e^{-\frac{(\Delta G^\circ+ \lambda)^2}{4 \lambda k_B T}} \tag{6.2} \end{equation}\]

where:

\[\begin{equation} |V(r)|=|V(r)|^\circ e^{-\frac{\beta(r-r_\circ)}{2}} \tag{6.3} \end{equation}\]

At first, and indeed second glance this equation can be overwhelming. There are a number of new terms in this equation, which we will break down further, however what is interesting is that a thermodynamic term (\(\Delta G^\circ\)) appears in our kinetic equations.

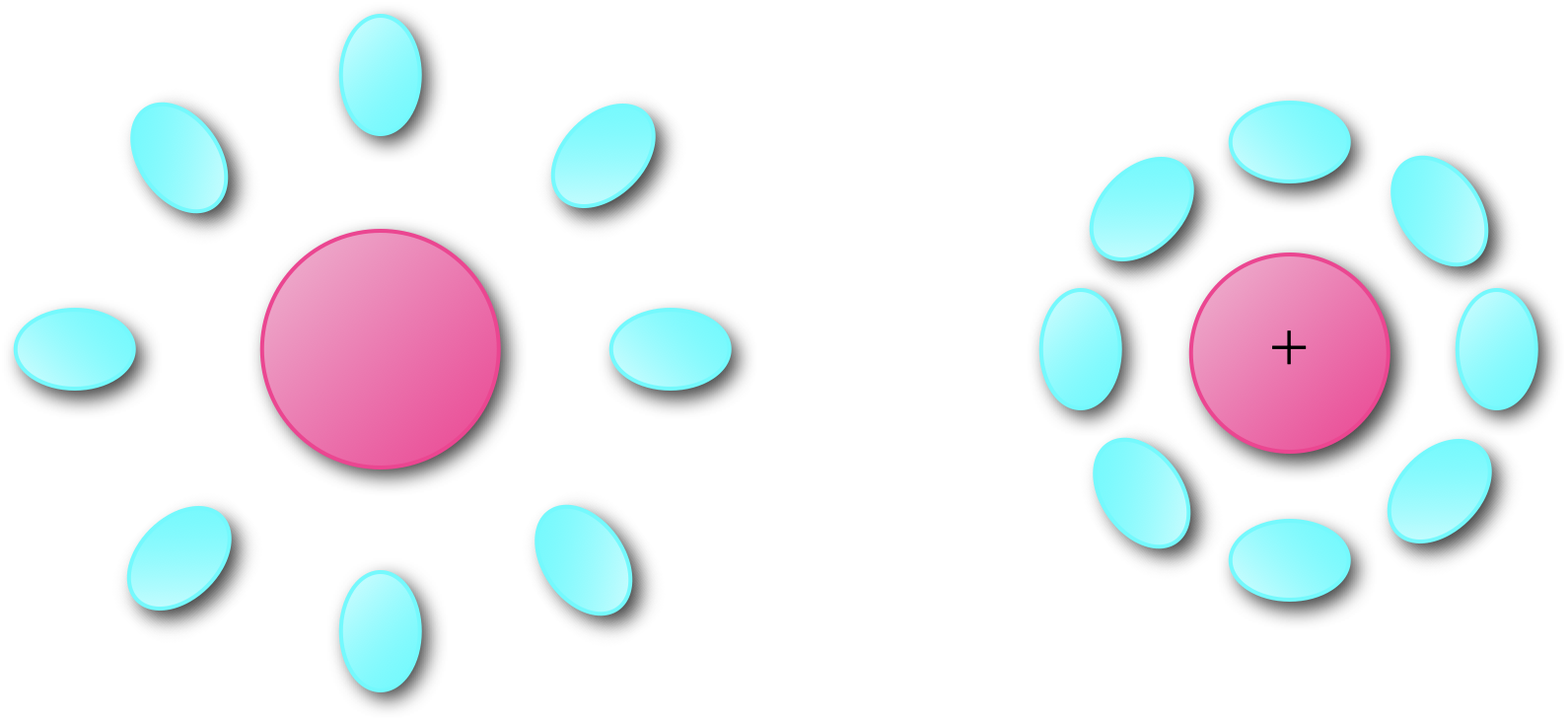

If we recall our discussion on Stokes shift (section 3.2 we introduced the idea of reorganisation of both the chromophore and solvent environment upon excitation of an electron from a ground to an excited state. There is a similar reorganisation of both chromophore and solvent upon either one electron oxidation (or reduction), figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6: Upon oxidation there is a reorganisation of both the molecule and its surrounding environment to minimize the energy of the structure.

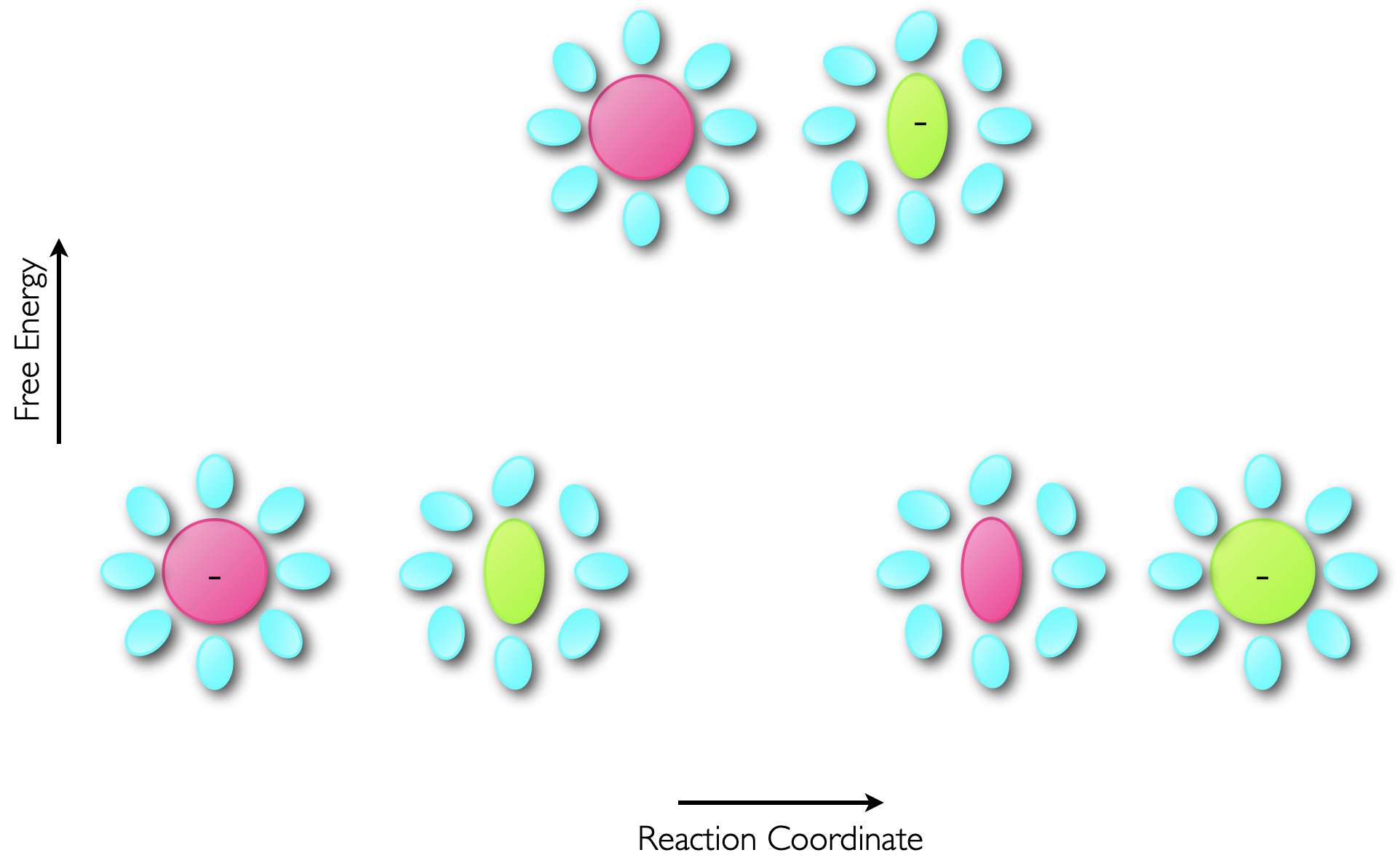

This electron transfer is essentially instantaneous, and using the same justification as was used when considering the Franck-Condon principle, upon transfer of an electron from a donor to an acceptor the product of the electron transfer between the two molecules initially has the same structure. This excited state then relaxes within a few picoseconds to optimise the states of the products, figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7: The transfer of an electron from a donor to acceptor occurs within a few femtoseconds, which is considerably faster than molecular vibrations (which occur on the ps timescale) so the electron transfer results in an excited state product which then reorganises to minimise the energy of the product.

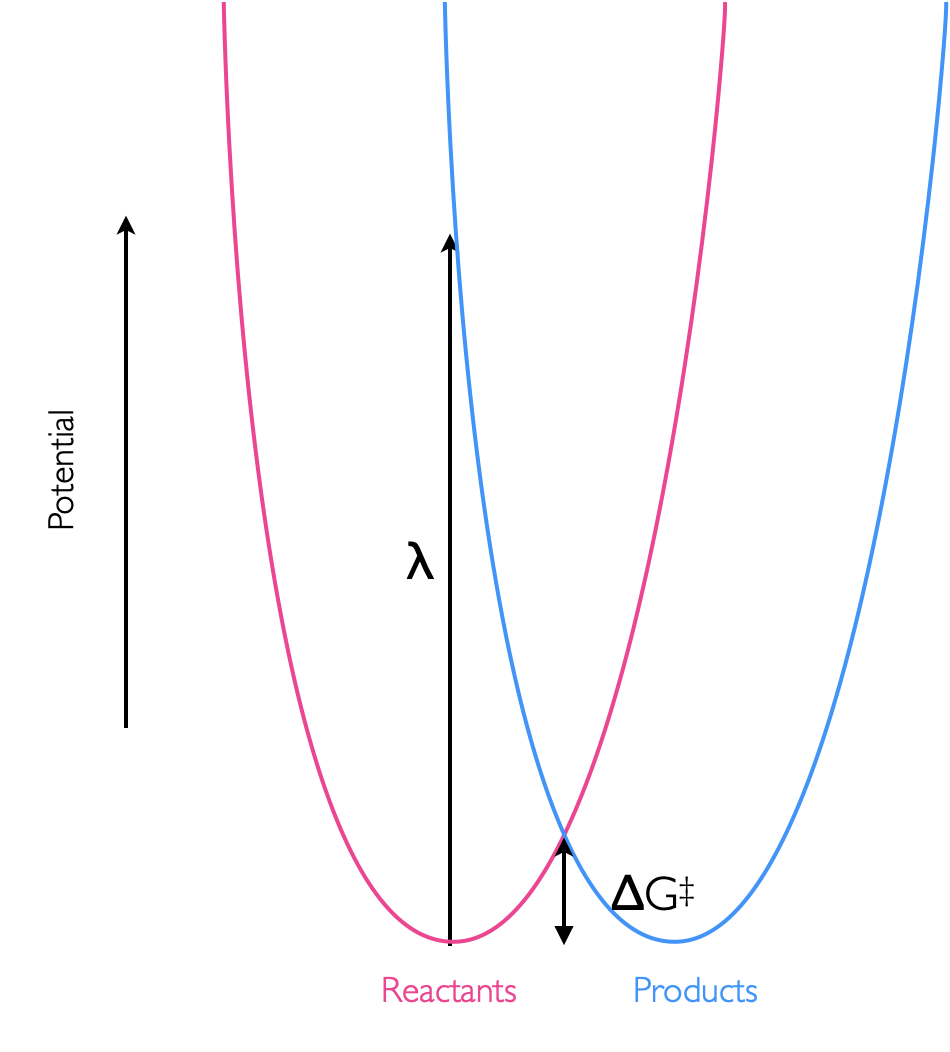

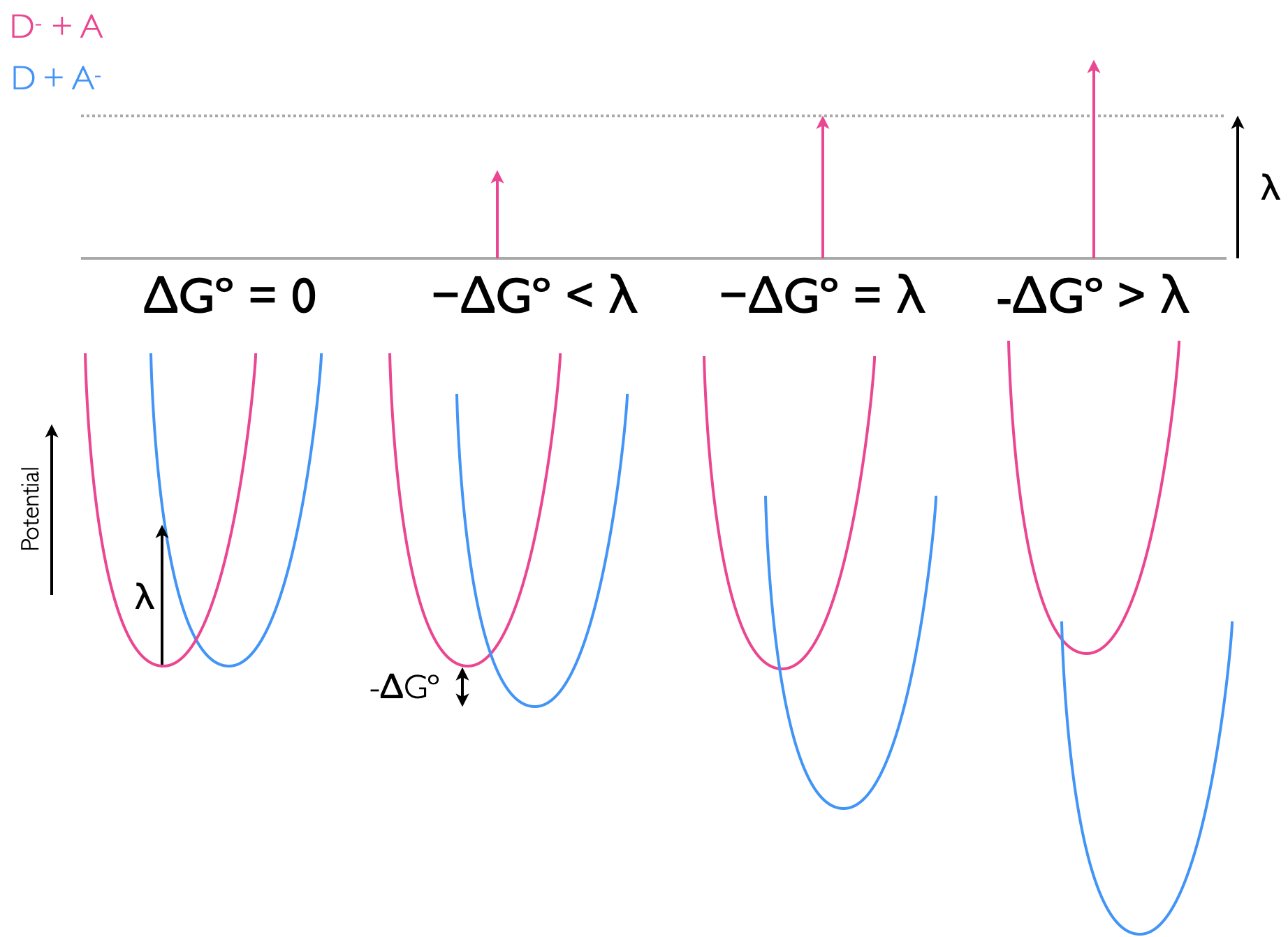

This energy is called the reorganisation energy, and appears with the symbol \(\lambda\) in equation (6.2). This reorganisation energy can be visualised by the vertical transition from the bottom of the potential energy well of our reactants to the potential energy well of the products, figure 6.8.

Figure 6.8: The reorganisation energy, λ, of an isoenergetic reaction, is the energy of the vertical transition between the potential wells of hte reactants and products. This reorganisation energy in this case is considerably higher than the activation energy of the reaction, ΔG‡

The final, as yet undiscussed term in the marcus equation (equations (6.2) & (6.3)) is the electronic coupling element \(|V(r)|\), this like the ‘overlap integral’ from before is a measure of the overlap of the molecular orbitals, but this time of the two states (reactant & product) of the donor and acceptor.

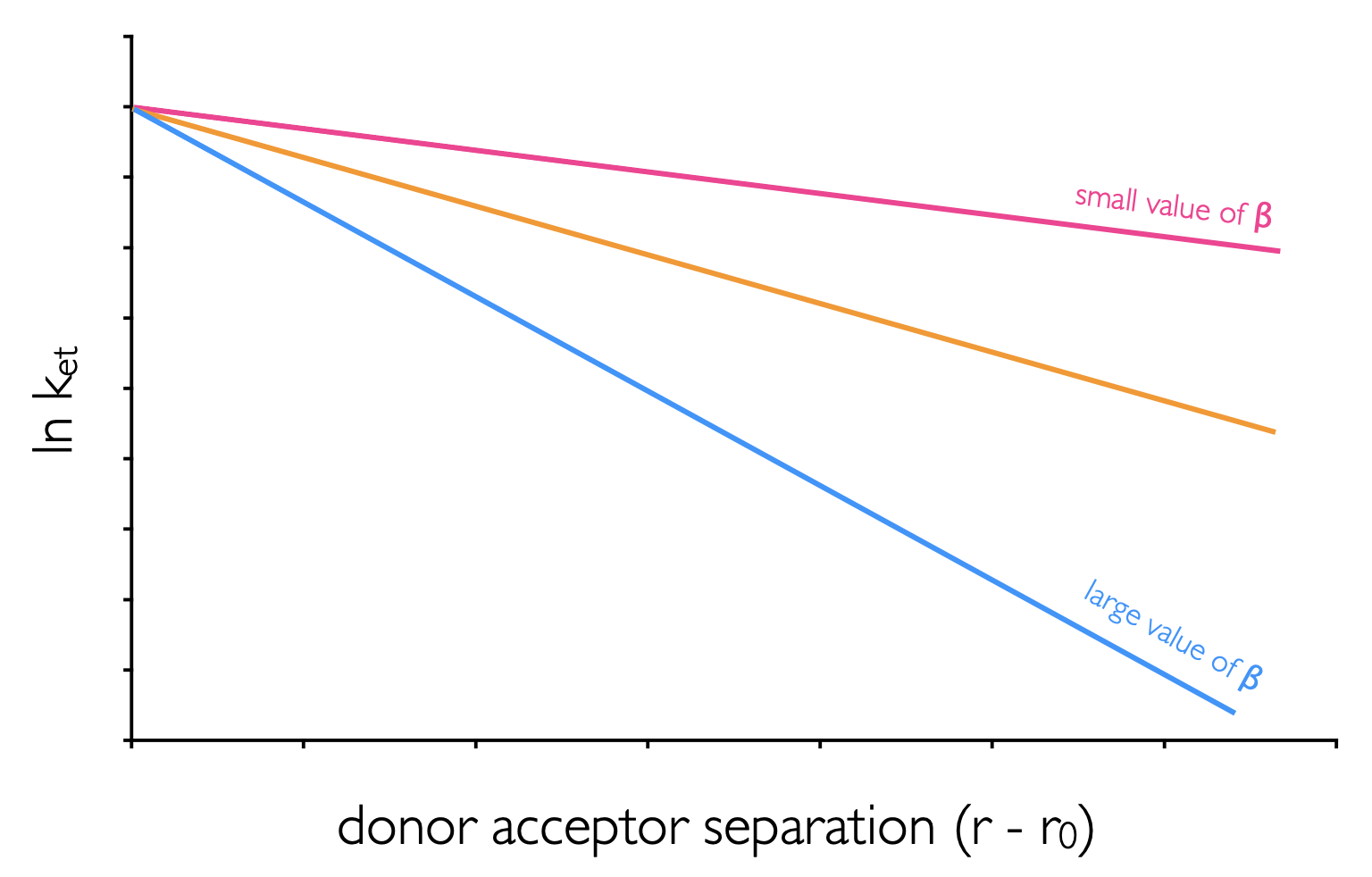

This value has a maximum at the van der Waals separation (\(r_o\) = 3.4 Å), and decreases exponentially with distance (\(r\)) (figure 6.9). The term \(\beta\) is a distance dependence scaling factor which describes how well the medium couples the donor and acceptor wavefunctions.

Figure 6.9: The distance dependence of electron transfer between donor and acceptor in mediums with different values of the distance dependence scaling factor, β.

Figure 6.8 shows an isoenergetic reaction, where the driving force of the reaction, \(\Delta G^\circ=0\). The transition state energy (the energy of the activation barrier) is related to the reorganisation energy, \(\lambda\) with the relationship shown in equation (6.4).

\[\begin{equation} \Delta G^\ddagger_{\textrm{et}}=\frac{(\Delta G^\circ_{\textrm{et}}+ \lambda)^2}{4\lambda} \tag{6.4} \end{equation}\]

This gives two special cases, for the isoenergetic reaction where \(\Delta G^\circ=0\) the activation barrier \(\Delta G^\ddagger=\frac{\lambda}{4}\). Then for the case where the driving force of the reaction, \(\Delta G^\circ=\lambda\), then the activation barrier \(\Delta G^\ddagger=0\), and there is no barrier to the reaction occuring, figure 6.10.

Figure 6.10: The electron transfer between donor and acceptor with differing driving forces ΔGº, the potential energy wells of reactants (pink) and products (blue), with the reorganisation being the vertical transition from the bottom of the reactant well, and the activation energy, ΔG‡, being that from the bottom of the reactant potential well to the point where the two potential wells cross.

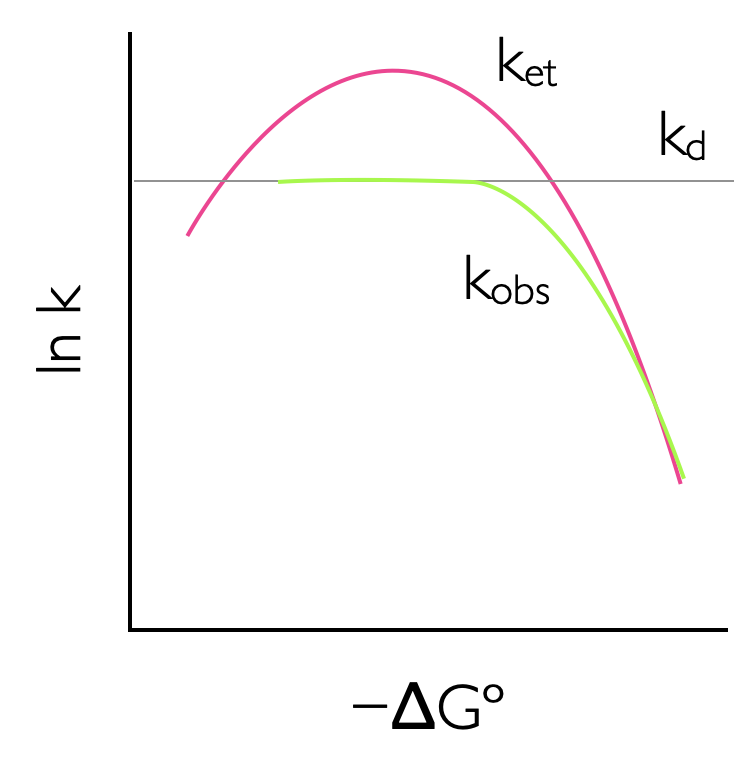

This leads to an interesting effect, as the driving force of a reaction increases the rate also increases until the point where the driving force and the reorganisation energy are the same. After this point the rate of reaction slows down, and this is perhaps an unusual and unexpected result. However, reaching this ‘Marcus inverted region’, which typically requires a driving force of around -250 kJ mol-1, is diffiuclt, and only photochemical (or electrochemical) reactions, where additional energy is provided to increase the driving force have so far been found to reach this Marcus inverted region, 6.11.

Figure 6.11: The rate of reaction increases with increasing driving force to a maximum where -ΔGº = λ, where the rate of reaction reaches a maximum. As the driving force of reaction increases teh rate of electron transfer slows down due to increasing solvent and molecular reorganization effects, this is called the Marcus inverted region. This effect is attenuated if the reaction is diffusion controlled as the rate of diffusion is often slower than the maximum possible rate of electron transfer.

If the reactants in the donor acceptor electron transfer system are not held in rigid structure they then may diffuse together. This may ameliorate the possible rate of electron transfer (k_)as the observed rate of reaction is attenuated by diffusion effects (with rate \(k_\textrm{d}\))as described in equation ((6.5)).

\[\begin{equation} k_\textrm{obs}= \frac{k_\textrm{et}k_\textrm{d}}{k_\textrm{et}+k_\textrm{d}} \tag{6.5} \end{equation}\]

To observe the Marcus inverted region working in rigid or viscous solvent where diffusion is limited is one possibility, or else using a rigid scaffold to hold rigidly the donor and acceptor is also another way to observe this phenomenon. However, the Marcus inverted region is infact mostly likely to be observed in charge recombination reactions5.

6.5 Electron transfer reactions in DNA

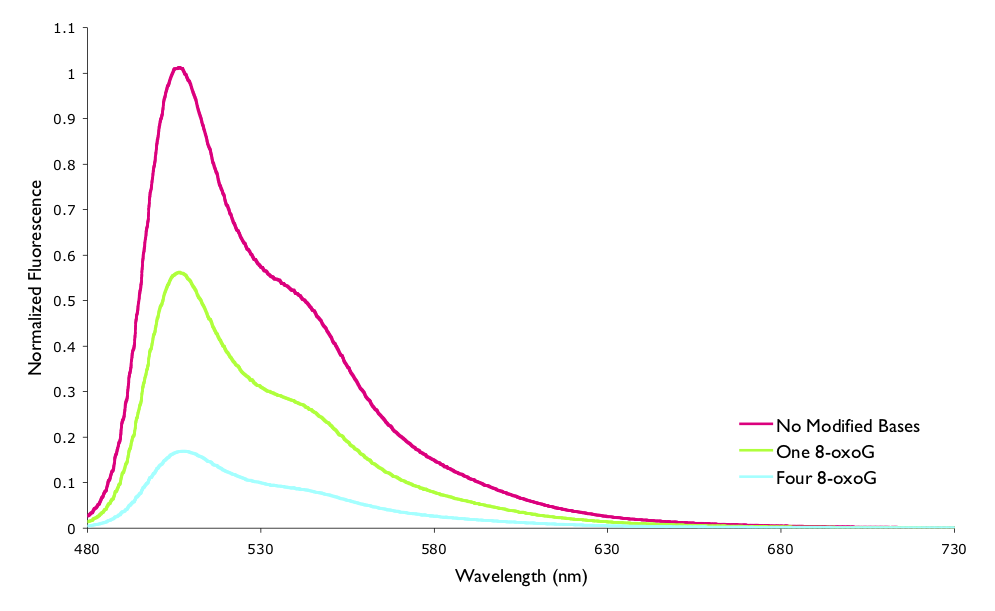

The assymetric cyanine dye YO-Pro-1 has been shown to fluoresce when bound to DNA, but further this fluorescence decreases over time. This decrease in fluorescence has been shown to be due to one electron oxidation of the modified base 7,8-dihydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine (8-oxoG) reducing the chromophore and quenching the excited state. The reaction was studied by both steady state and time resolved fluorescence techniques (figure 6.12 and table 6.1).

Figure 6.12: The measured normalised steady state fluorescence of YO-Pro-1 when bound to a 15mer oligonucleotide of DNA. The sequence of DNA variously had no modified bases, one 8-oxoG, or four 8-oxoG lesions.

| Normalised Fluorescence | \(\tau\) / ns | \(\tau / \tau_0\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| no modified bases | 1 | 2.80 | 1 |

| 1 8-oxo-G | 0.558 | 2.38 | 0.85 |

| 4 8-oxo-G | 0.169 | 1.31 | 0.47 |

You will recall that in Section @ref({sec:ratesphoto}) the lifetime and quantum yield of a process were introduce, and it was stated that the ratios of both the lifetime and fluorescence intensity of the quenched to unquenched systems should be the same, however it is clear from the values in Table @ref{tab:YOquench} that this is not the case.

However, the lifetimes listed are actually multicomponent (there are multiple first order exponential decays overlayed), of which the instrument used could only measure longer lifetimes (> 0.8 ns). If the system is instead modeled as being a ladder with the modified base and dye held rigidly in one of a number of distance separations then the ‘calculated normlalised average lifetime’ and the normalised fluorescence take the same values.

This case has been mentioned here to highlight limitations of measured lifetimes where the instrument used has to be suitable for the lifetimes you are measuring. It also highlights that Marcus theory is useful even if we are not interested in the Marcus inverted region.

If you wish to learn more about systems where there is more than one component in the emission, and what this means the unit CH40227 discusses such systems.

6.6 Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a photosensitised redox process whereby plants and some micro organisms convert carbon dioxide to carbohydrates and other organic molecules. The general reaction scheme is:

\[\begin{equation} \textrm{nCO}_2+ \textrm{nH}_2\textrm{O} + h \nu \longrightarrow \textrm{(CH}_2 \textrm{O)}_\textrm{n}+ \textrm{nO}_2 \tag{6.6} \end{equation}\]

at standard temperatures this reaction is very exergonic (ΔG ~ +500 kJ mol−1), and the chemistry involved in the process is very complicated but some key concepts are described here.

Principally it is a 4 electron process, the two half reactions are:

\[\begin{equation} 2\textrm{H}_2\textrm{O} \longrightarrow \textrm{O}_2 + 4\textrm{H}^+ + 4\textrm{e}^- \tag{6.7} \end{equation}\]

\[\begin{equation} \textrm{CO}_2+ 4\textrm{H}^+ + 4\textrm{e}^- \longrightarrow \textrm{(CH}_2 \textrm{O)}^+ + \textrm{H}_2\textrm{O} \tag{6.8} \end{equation}\]

There are a number of different steps in photosynthesis, which can be broken down into two classes of reaction. Light reactions (reactions requiring the input of a photon) involve the production of oxygen and dark reactions (reactions not requiring a photon) use the electrons and protons gained from the light reactions in order to reduce the carbon dioxide.

In order to harvest light for the reactions plants have a number of pigments, which cover a broad range of the visible spectrum. The pigment chlorophyl consists of a porphyrin ring ligated to a magnesium centre. In addition to chlorophyl plants have other conjugated molecules in order to harvest other wavelengths of light. These carotenoids principally absorb blue and green light which then transfers to the reaction centre, however these carotenoids also act as quenching agents in order to ‘hoover up’ any stray oxidising agents (principally singlet oxygen).

Charge separation in photosynthesis is incredibly important process, and is perhaps the most difficult step to replicate in artificial photosynthetic systems. There are also difficulties large structural changes and the large driving force required in order to replicate photosynthesis. Nature uses two reaction centres and harvests light from other antenna modules and currently artificial systems have no where near this complexity, however this is a leading topic of research and a number of different systems, either inspired by or totally removed from nature are currently being developed.

This has been an introduction to photosynthesis, but you should now read pages 222-232 or Wardle.

6.7 Photodynamic Therapy

Current research in photochemistry isn’t solely interested in light harvesting; there is also a large interest in using light in medicine. The most obvious biological use of light is in the essential production of vitamin D, however there are a number of unwanted photoactive reactions that occur, since both DNA and proteins may absorb UV light.

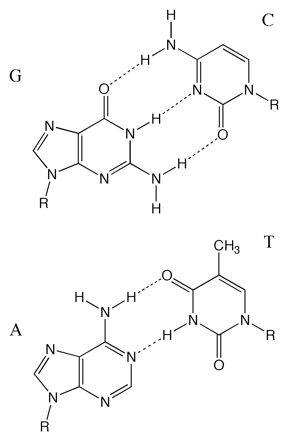

Figure 6.13: The base pairs in DNA, the purines guanosine and adenosine hydrogen bond to the pyrimidine bases cytosine and thymidine respectively. Conjugation in the bases means they all have good absorptions of around 6600 M−1 cm−1 at 260 nm.

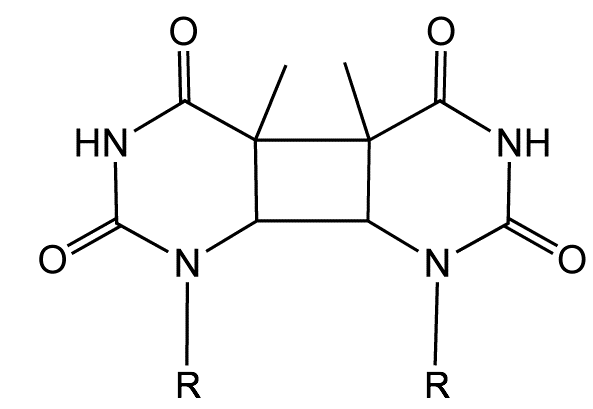

DNA undergoes a range of photochemical reactions, depending on the excitation wavelength, with either pyrimidine dimers (figure 6.14) or one electron oxidation of guanine forming the lesion 8-oxo-guanine being the principle products. Both of these adducts lead to mutations when replicating DNA, although there are a number of repair pathways mutations are inevitable. The pyrimidine dimerisation is particularly efficient as the reactants are already held closely together in the DNA structure.

There has been a great deal of interest in the field of phototheraputics; or using light in a medicinal context. The molecule methylene blue has been used for a number of years a sterilising agent as it is an efficient sensitiser of singlet oxygen, the blue colour is indicative of absorption of red wavelengths of light which makes it useful therapeutically as blood transmits red light. In fact methylene blue has undergone field trials for photosterilisation of blood products in remote areas. The concept being blood products need all DNA removed, wether pathogens or donor white blood cells, methylene blue is indiscriminate in the photosensitised oxidative reactions and any easily oxidisable reactant is damaged.

Figure 6.14: The structure of a thymidine dimer adduct formed by absorption of UV light.

Using a slightly more targeted approach a number of molecules have been developed for use in photodynamic therapy for treatment of conditions such as cancer. Traditional chemotherapies make use of the higher metabolic rate of cancerous cells and a generally not very specific, which is the reason for the large number of side effects. Photodynamic therapy hopes to use a drug which is completely non toxic in the ‘dark state’ but upon absorption of a photon the molecule becomes highly reactive to either DNA or proteins. Since light can be easily directed only the treated area is generates toxins, however this means that only accessible regions such skin and lungs may be treated. An ideal photodynamic agent will be blue (have a red absorption) so that the light may be transmitted through the skin and blood vessels and will be highly active. Cells have a number of ‘anti oxidant’ repair mechanisms and so damage has to be significant so as to either stop cell replication or cause apoptosis.

There are a number of papers which show the Marcus ↩︎