CH101371 Week 1 - Part 1: Preliminaries

The ‘content’ videos are all very short, any equations or important images are contained in the text of this document and so pdf slides will not be shared (as these are not an accessible document).

1.1 Why thermodynamics matters

The laws of thermodynamics are some of the most fundamental laws of nature, and in this course I hope you will learn to understand these laws and be able to apply them to explain the world around you.

Thermodynamics is fundamental to the way we live, to our dream of living a better, less impactful life and to how we as ‘life’ work.

1.2 State functions - (products - reactants)

Many properties in thermodynamics are state functions, that is properties that only depend upon the current state of the system. State functions are completely independent of the path by which that final state was reached.

Enthalpy (\(H\)) is a state function, as are entropy (\(S\)), internal energy (\(U\)), Gibbs’ free energy (\(G\)), Helmholtz free energy (\(F\)), temperature (\(T\)), pressure (\(p\)), and chemical composition.

Path functions are unlike state functions in that they depend on the path taken to determine their value. Heat (\(q\)) and work (\(w\)) are both examples of path functions.

Internal energy, \(U\) The internal energy is the sum of all of the kinetic and potential energy contributions of the molecules in the system.

Enthalpy, \(H\) The enthalpy is related to the internal energy, but also takes into account any expansion work done by the system, formally ΔH = ΔU + Δ(pV).

Entropy, \(S\) The entropy is a measure of the number of possible arrangements of a system (multiplicity, \(Ω\)), formally \(S = k_B \ln Ω\)

Gibbs’ free energy, \(G\) The Gibbs’ free energy is a measure of the energy available to ‘do work’ in a reaction system. It accounts for both the enalpic and entropic contributions of the reaction. \(\Delta G = \Delta H − T \Delta S\)

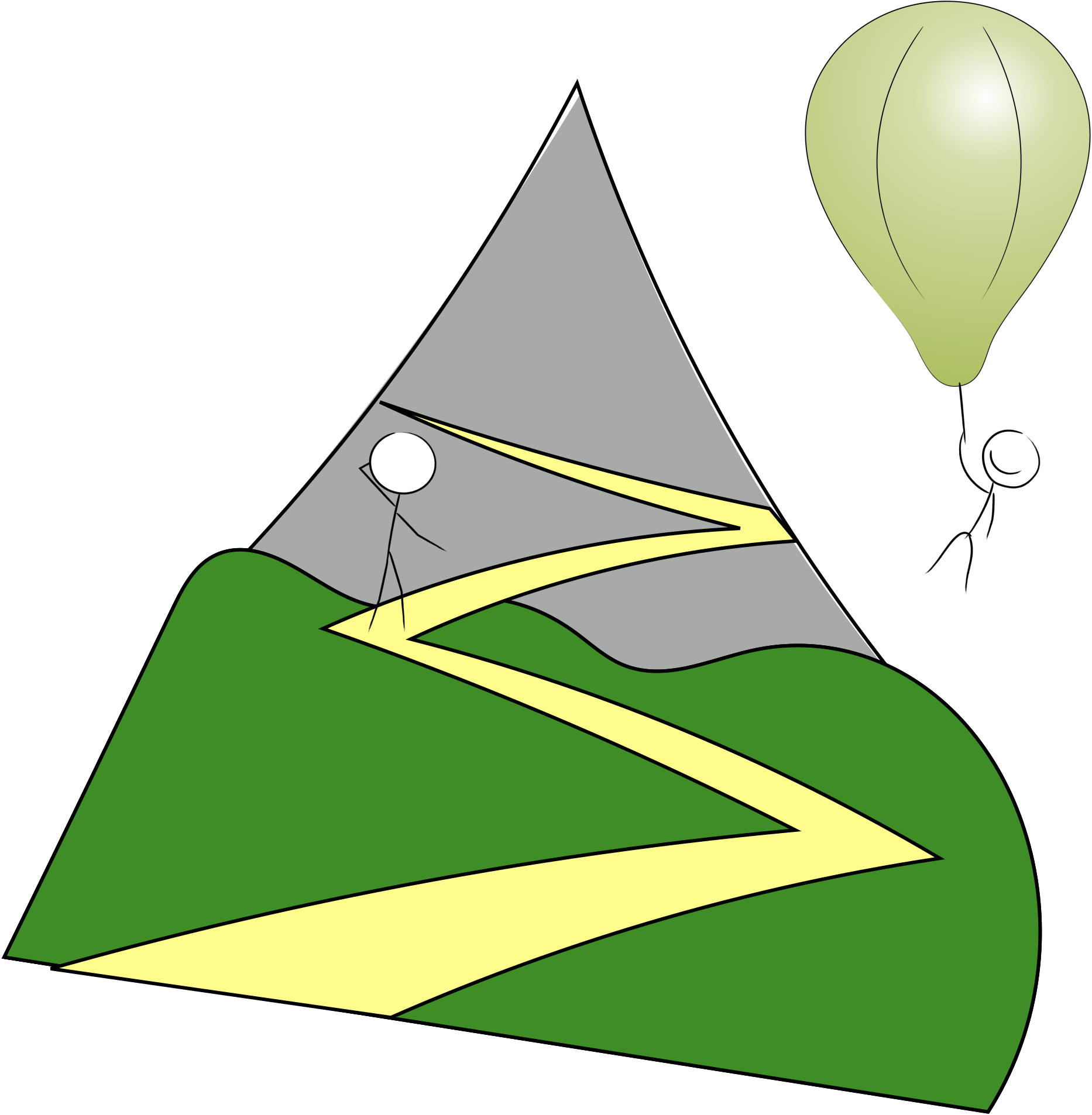

Figure 1.1: State functions - no matter how you got here, here you are… …altitude is a good analogy for a state function, whether climbing the mountain or flying on the balloon if your altitude is 1000 m it is 1000 m!.

1.2.1 Useful equations - State functions

Hess’ Law (Equation (1.1)) is something most will be familiar with already. You should try to think about it in terms of an equation however, not the cylces of which you may already be familiar.

\[\begin{equation} \Delta_r H^{\ominus} = \sum_{products}v \Delta H^{\ominus}_\textrm{X}-\sum_{reactants}v \Delta H^{\ominus}_\textrm{X} \tag{1.1} \end{equation}\]

Similar equations can be used for heat capacity (Equation (1.2)), this equation for heat capacity will then be used later in the course when we look at the effect of temperature on the enthalpy and entropy of reaction.

\[\begin{equation} \Delta_r C_p^{\ominus} = \sum_{products}vC_{p,n}^{\ominus}-\sum_{reactants}vC_{p,n}^{\ominus} \tag{1.2} \end{equation}\]

Entropy, just like enthalpy is a state function.

\[\begin{equation} \Delta_r S^{\ominus} = \sum_{products}v S^{\ominus}-\sum_{reactants}v S^{\ominus} \tag{1.3} \end{equation}\]

As is Gibbs’ free energy.

\[\begin{equation} \Delta _ r G^\ominus = \sum_{prod} v G_n^\ominus - \sum_{react} v G_n^\ominus \tag{1.4} \end{equation}\]

The value of each of these variables is independent of the path used to form them. Hence, the same ‘products − reactants’ approach always works!

1.3 Types of thermodynamic system

When we consider anything in thermodynamics we have to consider both the system and its surroundings. The relationship between the system and the surroundings defines the different types of thermodynamic system.

1.3.1 Isolated system

Figure 1.2: Isolated system: there is no exchange of matter or energy between the system and surroundings.

In an isolated system, there can be no exchange of either matter or energy in any form between the system and surroundings.

A stoppered perfectly insulated flask may be thought of as an isolated system.

1.3.2 Open system

Figure 1.3: Open system: in an open system both matter and energy may be exchanged between the system and surroundings.

In an open system both matter and energy can be exchanged between the system and surroundings.

A cup of tea is a nice example of an open system you can add sugar (if you are weird), drink it, or forget about it and find it cold 2 hours later.

1.3.3 Closed system

Figure 1.4: Closed system: in a closed system only energy in either the form of heat or work may be exchanged between system and surroundings..

A closed system is one where you can’t exchange matter but energy in the form of either ‘heat’ or ‘work’ can be exchanged between the system and surroundings.

A closed system is often used as a simpler model than an open system - not many things in life actually fit this model perfectly, but most bench chemistry where we can heat a system fits into this model.

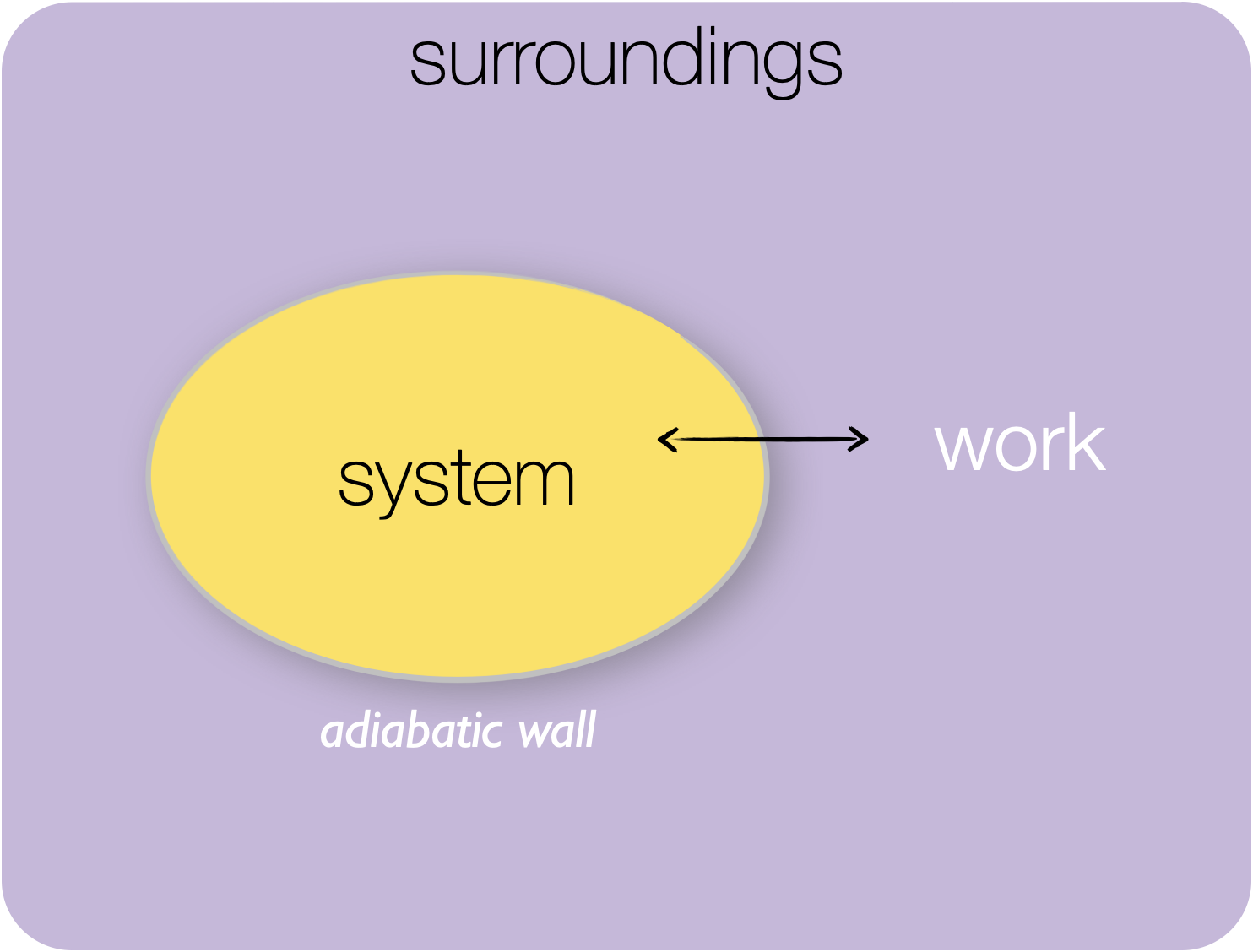

1.3.4 Adiabatic system

Figure 1.5: Adiabatic system: in an adiabatic system only energy in the form of work may be exchanged between the system and surroundings.

An adiabatic system is one where you can’t have any flow of heat between the system and surroundings, but you can exchange energy in the form of work.

This would mean that the system is insulated from the surroundings, and therefore the system may not be in thermodynamic equilibrium with the surroundings.

We will learn more about both ‘heat’ and ‘work’ later in the course.

1.4 Extensive and intensive properties

The difference between extensive and intensive properties is whether the property depends upon the amount of ‘stuff’ you have.

1.4.1 Intensive properties

Properties which are independent of the amount of stuff are called ‘intensive properties’.

Temperature is an example of an intensive property as are all of ‘molar’ properties (the quantity of something ‘per mole’): molar heat capacity, molar enthalpy, molar entropy, molar Gibbs’ energy, etc… in physics the term ‘specific’ is often used such as specific heat capacity and specific enthalpy, these are also intensive properties based on the fixed amount of a ‘gram’ (g).

1.4.2 Extensive properties

Conversely, properties which are dependent on the amount of stuff you have are called extensive properties.

Many intensive properties have extensive equivalents, so whilst we have the intensive property ‘molar heat capacity’ we also have extensive equivalent ‘heat capacity’; one looks at the amount of energy it takes to raise one mole of a thing by one kelvin, whereas the other looks at how much energy it takes to raise the temperature of how ever much of a thing we have by one kelvin.

Consequently extensive properties have different units to their ‘equivalent’ intensive property.

Other examples of extensive properties are unsurprisingly: volume, mass, amount (as in moles), and length.

Whilst knowing the terms extensive and intensive isn’t vital it is hugely important to recognise that sometimes terms will appear with different units to suit the particular situation.

1.5 Classical vs. Statistical thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is quite an old subject, much of our understanding of why chemical reactions happen is based in 19th century science. This understanding was based on emperical observation of things like steam engines and battery piles. It scientists trying to understand how things work in order to make them better, make them more efficient, and make them safer.

This 19th century (and earlier) view of the world didn’t even consider things we take for granted now, nowhere in thermodynamics do we ever really think about atoms. We talk about ideal systems (those that follow the rules nicely), but never really care about the reaction taking place, it is all just the bulk average behaviour of the system.

Then in the late 19th century Ludwig Boltzmann proposed a different way of thinking about thermodynamics. He started to think about the ‘average’ behaviour of individual atoms. This version of statistical mechanics gave an explanation of what concepts like entropy were and it helped explain macroscopic phenomena (such as pressure and temperature) on an atomic and molecular level.

Statistical thermodynamics started to be able to explain the values of what had until then been emperical constants.

Consequently in this course we will look at thermodynamics from both a classical and statistical point of view.

1.6 Degrees of Freedom

Perhaps unsurprisingly the structure of molecules is an important concept when we consider thermodynamics from the molecule up perspective, but perhaps surprisingly classical thermodynamics does not care at all the structure of the molecules in the system we are considering.

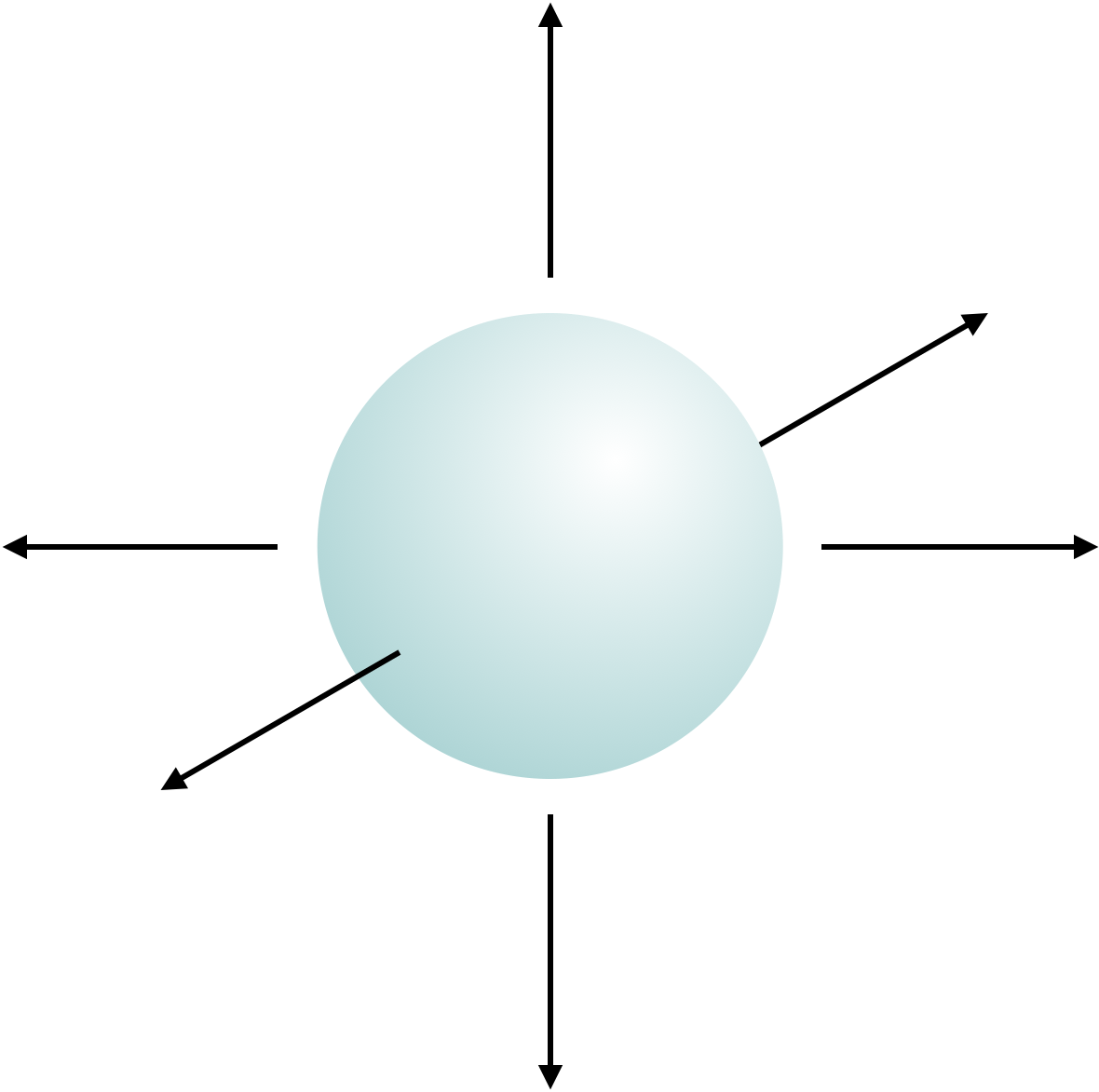

Figure 1.6: Every atom has three degrees of freedom, these are movement along the x, y and z axis.

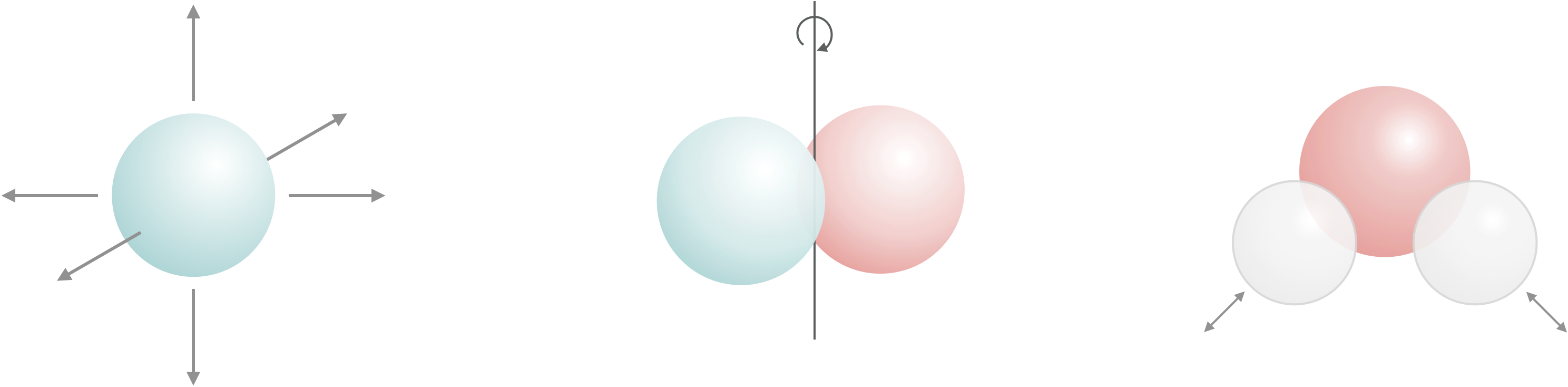

When atoms combine to form moleucules the total number of degrees of freedom must be conserved, and so new types of degrees of freedom are introduced, namely molecular rotations and molecular vibrations (figure 1.7, and equations (1.5) and (1.6)).

Figure 1.7: Translations, molecular rotations and molecular vibrations are all degrees of freedom.

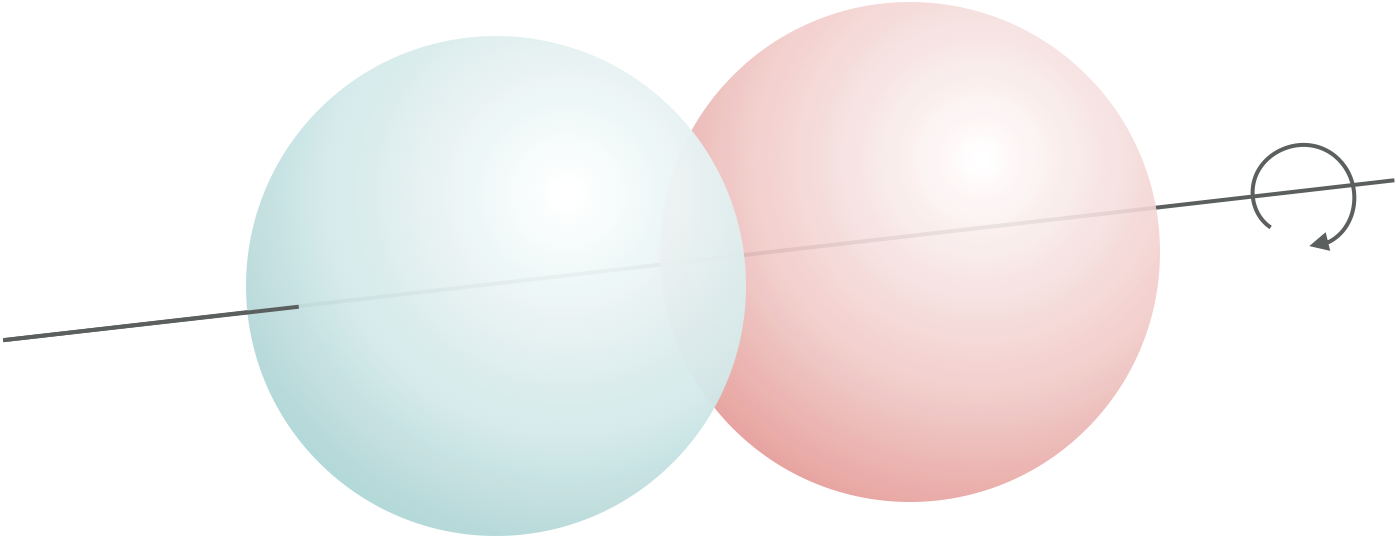

For linear molecules there are three translational degrees of freedom, two rotational degrees of freedom (figure 1.8) and the number of vibrational degrees of freedom is given by equation (1.5), where N is the total number of atoms in the molecule:

\[\begin{equation} x = 3N-5 \tag{1.5} \end{equation}\]

Figure 1.8: In linear molecules there are only two rotational degrees of freedom as rotaion around the z-axis (the long axis of the molecule) are equivalent and therefore dont contribute to the degrees of freedom.

For non-linear molecules there are three translational degrees of freedom, three rotational degrees of freedom and the number of vibrational degrees of freedom is given by equation (1.6), again where N is the total number of atoms in the molecule:

\[\begin{equation} x = 3N-6 \tag{1.6} \end{equation}\]

1.7 Example calculations

1.7.1 Example calculation - Hess’s Law

How much energy is released when 4.60 g of sodium reacts with excess water to give NaOH (aq) & H2 (g)?

- ΔHf⦵ NaOH = −425.61 kJ mol−1

- ΔHf⦵ H2O = −285.83 kJ mol−1

The enthalpy of formation of elements in their standard state (e.g. Na (s) & H2 (g)) is zero.

Therefore using equation (1.1):

\[\begin{equation*} \Delta H_{rxn}^{\ominus}= \Delta H_{f}^{\ominus}(\textrm{NaOH})-\Delta H_{f}^{\ominus}(\textrm{H}_2\textrm{O})= −425.61 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1} − −285.83 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1} = −139.78 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1} \end{equation*}\]

\(R_M \textrm{ Na} = 22.989769 \textrm{ g mol}^{−1}\) Therefore:

\[\begin{equation*} n \textrm{(Na)} = \frac{m}{R_M} = \frac{4.60 \textrm{ g}}{ 22.989769 \textrm{ g mol}^{−1}} = 0.200 \textrm{ mol} \end{equation*}\]

note sf!

Therefore if 4.60g reacts:

\[\begin{equation*} \Delta H_{rxn}^⦵ ( \textrm{kJ}) = \Delta H_{rxn}^⦵ ( \textrm{kJ mol}^{−1}) × \textrm{mol} = −139.78 \textrm{kJ mol}^{-1} × 0.200 \textrm{mol} = −28.0 \textrm{ kJ} \end{equation*}\]

The ‘−’ sign indicates that heat is released (evolved) and the temperature of the surroundings increases.

1.7.2 Example Calculation - Kirchoff’s law

Kirchoff’s laws may be used to adjust calculated values of enthalpy and entropy of reaction to different temperatures, they use the difference in heat capacity of products and reactants to do this. Determine \(ΔC_{p,m}\) for the following reaction:

CH3CH2OH (aq) + CH3COOH (aq) ⟶ CH3COOCH2CH3 (aq) + H2O (l)

| \(ΔC_{p,m}\) / J K\(^{−1}\) mol\(^{−1}\) | |

|---|---|

| CH3CH2OH (aq) | 111.46 |

| CH3COOH (aq) | 124.3 |

| CH3COOCH2CH3 (aq) | 170.1 |

| H2O (l) | 33.58 |

\[\begin{equation*} ΔC_{p,m \textrm{ rxn}} = (C_{p,m} \textrm{CH$_3$COOCH$_2$CH$_3$ (aq)} + C_{p,m} \textrm{H$_2$O (l)}) − (C_{p,m} \textrm{CH$_3$CH$_2$OH (aq)} + C_{p,m} \textrm{CH$_3$COOH (aq)}) \end{equation*}\]

\[\begin{equation*} ΔC_\textrm{p,m rxn} = (170.1 + 33.58) − (111.46 + 124.3) \textrm{ J K$^{-1}$ mol}^{−1}) = − 32.1 \textrm{ J K$^{-1}$ mol}^{−1} \end{equation*}\]

1.7.3 Example Calculation - Degrees of Freedom

Determine the number of degrees of freedom, and types of each, of ethanol CH3CH2OH.

Ethanol is non-linear molecule with 9 atoms. Therefore in total there are (3N) 27 degrees of freedom.

There will be 3 translational degrees of freedom (along the x,y&z axes),

there will be 3 rotational degrees of freedom (rotation around the x,y&z axes),

and there will be 3N-6 (because it is non linear) or 21 vibrational degrees of freedom.

1.8 Questions

Later in this course you will learn about the origin of these equations, for now it is enough to be able to balance chemical equations and use the fact that each of the variables in the following equations are state functions.

- What is the standard Gibbs’ free energy of the oxidation of ammonia (NH3) to nitric acid (NO)?

Hint: This is a redox reaction.

\(ΔG^⦵_{f, \textrm{NH}_3} = −16.45 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

\(ΔG^⦵_{f, \textrm{NO}} = +86.55 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

\(ΔG^⦵_{f, \textrm{H}_2 \textrm{O}} = −228.57 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

- Methanol fuel cells have been proposed as replacements for internal combustion engines. Methanol (density, ρ = 792 kg m−3) is reacted in a fuel cell to be completely oxidised.

Given the enthalpies of formation required are listed below determine the amount of energy released per mL of methanol.

\(ΔH^⦵_{f, \textrm{CH}_3\textrm{OH}} = −425.61 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

\(ΔH^⦵_{f, \textrm{H}_2 \textrm{O}} = −241.82 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

\(ΔH^⦵_{f, \textrm{CO}_2} = −393.51 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

- Ammonium dichromate decomposes upon heating in a spectacular ‘volcano’ reaction:

(NH4)2Cr2O7 (s) ⟶ N2 (g) + 4 H2O (g) + Cr2O3 (s)

Determine the enthalpy of reaction for this process given the following data.

\(ΔH^⦵_{f, \textrm{(NH}_4\textrm{)Cr}_2\textrm{O}_7\textrm{ (s)}} = −1810 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

\(ΔH^⦵_{f, \textrm{H}_2 \textrm{O (g)}} = −240 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

\(ΔH^⦵_{f, \textrm{Cr}_2 \textrm{O}_3 \textrm{ (g)}} = −1140 \textrm{ kJ mol}^{−1}\)

How would the enthalpy of reaction differ if liquid water was formed? Justify your answer.

1.9 Answers

- \(ΔG_{rxn}^⦵\) = −239.86 kJ mol−1\(_{NH_3}\) (per mole of NH3)

- \(ΔH_{rxn}^⦵\) = -11.2 kJ cm-3

- \(ΔH_{rxn}^⦵\) = -290 kJ mol−1, become more negative as heat is released upon condensing (we will cover this later in the course if you don’t understant this last part, please don’t stress).